29 Nov Seattle Freight Plan – Just in Time Delivery

Some are already making an argument to narrow the width of the new surface roadway that will line Seattle’s central waterfront after the Alaskan Way Viaduct is removed. Which is one reason to appreciate the business community volunteers, city staff and elected leaders who finally succeeded in enacting a City of Seattle Freight Mobility Plan.

Some are already making an argument to narrow the width of the new surface roadway that will line Seattle’s central waterfront after the Alaskan Way Viaduct is removed. Which is one reason to appreciate the business community volunteers, city staff and elected leaders who finally succeeded in enacting a City of Seattle Freight Mobility Plan.

Adopted in September, the freight plan classifies the waterfront road as a Major truck street. It also prioritizes its preservation as Seattle’s primary north-south truck route for oversize loads.

Mere existence of the plan does not guarantee how the city’s deliberative process will turn out for the waterfront roadway. But, the plan provides a clear public policy basis for maintaining the road as a major route to move goods and people between both ends of our hour-glass shaped city.

Mayor Murray and the City Council deserve praise for the plan – Seattle is one of only a few cities in North American that has a freight plan.

But, the list of accolades would be incomplete without including Warren Aakervik, the retired owner of Ballard Oil.

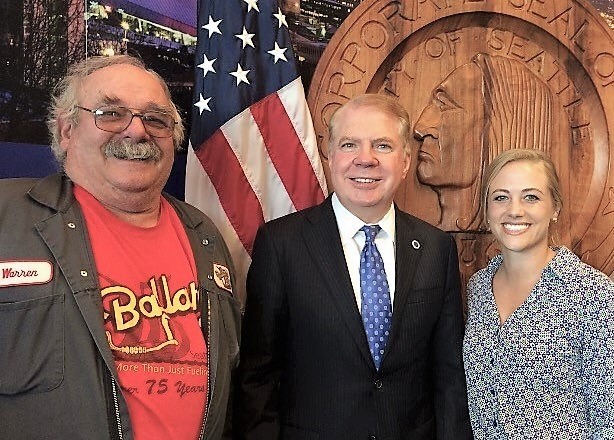

Warren is pictured above with Mayor Murray. Warren is the one in coveralls and a tee-shirt. Given the garb, you would probably be amazed to discover all those in the Emerald City, high and low, who promptly return his phone calls and emails.

His family roots run deep in the Ballard maritime community and at least two generations of elected leaders and government staff members have acquired windshield views of Seattle freight issues from the passenger seat of a Ballard Oil truck, Warren at the wheel, serving as their tour guide.

His viewpoint shows up time and again in the 109-pages of the freight plan. That’s no accident. It’s hard to imagine anyone outside city government who spent more time providing more input on these issues for more years.

Better than any city document that came before it, the plan articulates Seattle’s role as a regional hub for an amazing mix of trade transported by trucks, trains, ships and airplanes with economic impacts that are immense. The study cites state data estimating that 900,000 jobs in Washington are directly tied to the movement of freight.

But, the unusual quality of the plan arises from its continuing efforts to explain how freight supports the daily lives of Seattle residents. For instance, there is a comment that freight “is the process by which the latest gadget you ordered over the internet makes it from the warehouse to your doorstep.”

Another passage states that without freight, “the shelves in our local grocery stores and retail shops would be empty. We would be unable to receive and send mail and packages. Hospitals would be unable to procure highly specialized devices needed for medical procedures. Our cars and other vehicles would sit in driveways or in garages with empty gas tanks. Our homes would be unheated. Garbage, recycling, and compost wouldn’t be picked up. Freight transportation is critical to allow us to get the goods and services we need, when we need them.”

You might think it would be typical that a freight plan would include such language. But, freight plans typically don’t exist, and it is difficult to imagine Seattle would have one without Warren Aakervik.

Thanks also go to the City of Seattle employees who contributed to the effort including Gabriela Vega, Ian Macek, Chris Eaves and Sara Zora.

View the document online at:

http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/docs/fmp/FMP_Report_2016E.pdf